The Three Tiers of Worldbuilding in Disco Elysium

Note: this post contains relatively light spoilers for the main plot, but reveals several massive secrets you may discover in sidequests, particularly in the “Tertiary” section of this post. Continue onward at your own risk!

Recently I completed my first playthrough of a game called Disco Elysium by developer ZA/UM, which grabbed my attention like few games have in my adult life. At a high level, the premise is you wake up in a room with amnesia, and slowly unravel your identity while solving a mystery with serious political implications. The game distills classic Computer Role-Playing Game (CRPG, think games like Baldur’s Gate or Pillars of Eternity) gameplay down to the role-playing fundamentals: character creation, dialogue options, decision-making, and skill checks. Notably absent from that list is a formal combat system with attacks, health, mana or any other of the genre staples; the few instances of violence are managed through the games dialogue and skills systems. Leaving combat out of a game of this style is quite bold.

This boldness carries over into the game’s storytelling and worldbuilding, wherein the major plot points and background details that support the story are revealed largely through investigating the environment and discussion with non-player characters, rather than through exposition.

Worldbuilding, the art of creating the details of a fictional setting which support a story, is a topic near and dear to my heart. I have a habit of trawling through the wiki pages of various fictional properties, absorbing all of the details I can find that work together to form a setting. I attribute much of this fascination to the love of history and research that my father instilled in me. As a history teacher, he would always stress to his students - and to me, during the long car rides to school - that it was impossible to fully appreciate and understand why something is the way it is without understanding the how. What happened to get us to where we are? How do the problems of today reflect the solutions of the past?

We live in a world shaped by ghosts, molded by a multitude of decisions made by individuals long-dead before we’re even born. I’ve yet to see a game that is as effective at reflecting this aspect of our reality as Disco Elysium. The world is alive with detail, both those that paint the picture of “now” and those that show how things once were “then”. All together they do a remarkable job of answering just about every “how” and “why” I could come up with while I was playing.

The way the details are presented in Disco Elysium, and the world illustrated by them, line up well with an article I read recently: The 3 Tiers of Fantasy World-Building by Katie Bachelder. In that piece Bachelder examines different subgenres of fantasy through the lens of a three-tiered system of details. In summary, the facets of a fictional setting can be placed into categories, or tiers, ordered by how closely related they are to the central plot. The tiers are as follows:

- The primary is directly connected to the plot; the story cannot function without these details. It might set up the distinction between the antagonist and protagonist as well as help establish the stakes.

- The secondary is loosely connected to the plot. It might help explain the “why now” and the “why them,” as well set up where the story might go after the book itself is over.

- Lastly, there are the tertiary details. These are not important to the plot whatsoever, but instead serve to make the world feel more unique and fleshed-out.

I’ll provide an example of a tertiary detail, one utterly inconsequential to the plot that still introduces some flavor to the world. Once you get going on your investigation, you have the option to look into a nearby vehicle, where you may find something interesting. The car doesn’t have a steering wheel, but has an array of steering levers instead!

This may not be the first divergence you notice, but it exemplifies a trend in how the writers chose to blend the familiar with the unfamiliar in their setting. Everyone playing the game likely knows what a car is, so the nice twist on what’s expected helps make the unique details of the setting stand out because the player has context to notice the difference. Little details like this, while not always significant to the plot, are signals that the place your character is standing in is truly another world, despite some similarities.

This concept of categorizing details inspired me to point the same lens towards Disco Elysium as a study in worldbuilding. I found something surprising as I categorized the setting’s details by their importance to the plot. The further I got from the “primary” facts, the more I found that the creators of Disco Elysium hid some of the most earth-shatteringly critical truths about their setting in the most tertiary of details.

What follows is an examination of three aspects of the game world: the primary immediate details of the district of Martinaise where you spend the game hunting for clues, the secondary historical facts about the revolution in the larger city of Revachol, and the tertiary tidbits of information that cover Her Innocence Dolores Dei and “The Pale.”

Primary - You, Yourself, and Martinaise

You awake in a void, engaged in conversation with your Ancient Reptilian Brain as you slowly recover your senses. As the world filters in, you realize you are now at the beginning of what may be the worst hangover in history. You are in a room, the wreckage of the furnishings strewn throughout.

Who are you? Given the third person perspective of the game, you can clearly see that your character is a human, though that only gives you so much to work with. You can try to piece together your identity further through environmental clues. It’s here that the worldbuilding begins, much of it shown through optional interactable points of interest. A record player, rendered inoperable through damage. Someone’s necktie, likely your own, hanging from a spinning ceiling fan blade. Broken window, stained couch, a grimy bathroom and a door out into the hallway. What can we glean from all this, besides that your character may have made a few mistakes in life?

The society you find yourself in resembles Earth’s to some degree in that they have buildings with the standard array of features: walls, windows, floors, furniture, and even bathrooms with a toilet, mirror, and a tub. Music exists, with technology at least on par with the early 1900s using playable records. Electricity-powered ceiling fans were invented in the late 1800s, becoming commonplace after the first few decades of the following century. As far as you can tell, you could be in a one of many apartments on Earth in approximately the first half of the twentieth century.

Stepping outside, you find yourself on an interior balcony, overlooking what seems to be a cafeteria with tables and seats arrayed across the room. You encounter a young woman, and through optional conversation with her, you begin to put together more snippets of information regarding who and where you are. From song titles to cigarettes, your talks with this woman and others in the building rapidly establish the immediate cause and effect for why you’re here. You’re in a hotel, you’ve been here for several days on a tremendous alcoholic bender, and oh yeah, you’re a cop investigating a murder. Woah.

This seems like a great place to address the storytelling and game design choice to make the character have amnesia. A major selling point of story heavy games like most CRPGs is the ability for players to really throw themselves into a world, vacuuming up every detail through inspection of environmental details, documents and conversation with Non Player Characters (NPCs). If the designers choose to present setting details through dialogue, they implicitly have to answer a critical question: why does your character not know this information? Important things, like how magic works, who or what rules your area, or what major events have happened in the distant or recent past. It could seriously hamper the player’s suspension of disbelief if your character is a resident of a city, yet knows nothing about it as demonstrated by the questions your character may ask.

Writers handle this in different ways, and it isn’t an issue solely exclusive to gaming. When you’re writing a story in a setting other than the real world, you have to decide how you present critical setting information to the audience. One way to work around the problem is through narrator-led exposition, a “Voice of God” simply telling you of foreign concepts or in-universe historical events, though you risk disengaging the audience from the present-tense of the story you’re trying to tell. You could have one character directly explain a concept to another, but then you have to answer that tricky question as to why one character does not have that information.

An adult describing an idea or fact to a child is a popular choice, as children can reasonably be expected to be ignorant of certain concepts until they have been presented to them. Similarly, many stories choose to have the protagonist be from a far off land or a remote backwoods village, giving them an excuse as to why they would unfamiliar with the local setting of the story.

The writers of Disco Elysium took a different path. Your character is known by those around him, his past actions fully integrated into the setting. He’s a resident of the city you’re in, though not of the particular district, and he has an entire history that intersects with the people around him. How can you most effectively let a player slip into this character’s shoes, when there’s so much that character should be bringing to the table that the player does not know? How do you enable the player to ask questions to establish the setting, as is a standard for the genre, without making it impossible to believe the character would not know this information? Give him amnesia.

With such a blank slate, the player can simultaneously learn who their character is as they learn about the world they live in. An interesting game feature that adds to this experience is the skill system, which lets you build proficiencies in different categories both mental and physical. You build the character both through your actions and your investment in skills and particular thoughts that may open up additional options down the road, with the caveat that he is a defined person with certain limits on his role in the world. One particular skill, Encyclopedia, was very helpful when writing this article, as it lets you summon interesting non-essential factoids from deep within the depths of your alcohol-soaked mind at opportune moments. The challenge of balancing between letting the player mold the person they want to play as, but still leaving in bounds that limit the scope of who that character is in the setting, is fascinating.

Emerging from the hotel with your blank slate partially filled in, more details of the world emerge. Paving, architecture, citizens going about their lives. You learn you are in a district named Martinase, a subdivision of the greater city of Revachol, and you may quickly piece together that the place has fallen on hard times. Refuse - which you can even pick up and turn in, they recycle here! - and graffiti litter the landscape, showing that authorities who might be concerned about such things rarely interfere here. The deprived, almost broken-down character of Martinaise plays a central role in shaping the NPCs you interact with as you investigate the murder - for example, few are immediately willing to aid you, as experience has taught them to be distrustful of authority figures who have little interest in improving the conditions in which the live.

A variety of cargo vehicles are stuck in horrendous traffic - commerce does have a place here, as do delays, unfortunately. Why are they stuck? Following the traffic to its source, you find a protest, specifically a group of workers striking to prevent cargo from going in or out. The principal figure preventing anyone from getting through is a tremendously muscular racist named Measurehead.

Why do I call him racist? Well, he openly admits to being a racial supremacist, launching into a remarkably detailed diatribe about how certain races - his own among them, coincidentally enough - are superior to others almost immediately upon meeting the playable character. This is a highly charged situation you’ve walked into with loads of names and places being thrown around, which can be a lot to absorb, but is a treasure trove in terms of details about the world and how other people view it.

That last bit, the lens through which a person views the world which highlights certain aspects of that world due to their own opinions about what is right and wrong, feeds perfectly into the next topic: politics and how they mold the world your character finds himself in.

Secondary - Race, Politics, and the Revolution

The primary details concern who you are, where the story takes place, and why you’re there. Though Disco Elysium spends quite a bit of time discussing the people, cultures and ideas that populate its fictional world, these facts are not essential to understanding the immediate plot - at least, not at first. What these details do is set up why Martinaise, and greater Revachol, is the way it is and explain how the forces of history and politics created the setting in which the story takes place.

Let’s return to the discussion about the racist. Measurehead describes, in excruciating detail, an elaborate self-constructed system of categorizing and dehumanizing entire swathes of people based on their racial origin. Beliefs quite similar to Phrenology, a profoundly discredited pseudoscience that posits that you can infer facts about a person or race’s character from the shape of their cranium, even make an appearance!

If you’re familiar with some of the more disappointing parts of our own world’s history, you may find his maddening descriptions of how the Semenese people are anthropometrically superior to the Occidentals and how the mixing of races should be looked upon with disdain reminiscent of the Casta system for racial classification. Established by European occupiers of Latin America, the “purity of blood” could in some cases be measured down to absurdly miniscule fractions in order to determine someone’s place in a racial hierarchy, though the degree to which those myopic classifications affected people in practice have been debated.

You may also note that people of the various racial lineages described within Disco Elysium appear, on a surface level, to share physical features with actual races on Earth. Your partner in the investigation Kim Kitsuragi is coded as Asian, the racial supremacist Measurehead is dark-skinned and could be interpreted as being of African descent, and the playable character appears to be Caucasian. This casting of real-world races into fictional ethnicities is a more extreme example of the “car with levers” mentioned previously, building context through familiarity but introducing a twist that supports the worldbuilding.

Similarly, certain names and terms used in Revachol have a distinctly French character - a principle location in the game is named “Rue de Saint-Ghislaine”, for example. Through conversation with Measurehead and other, much more reasonable, people about cultural groups and their movements you can start to construct a history as to how the different cultures depicted ended up where they are at present in the game world, and how individuals perceive their successes and failures.

Perception becomes critical when examining the history of Revachol itself. Heading back away from Measurehead and his crackpot racial theories, meandering through the snarl of traffic, you will likely happen upon a towering statue of a rather important-looking man mounted astride a glorious steed, frozen as the horse rears back on its hind legs. The statue, while still standing, is arrested in a state of partial disrepair, with its internal structure exposed in several areas. What you may soon discover by speaking with the locals is that this statue was purposefully reconstructed to appear this way, as a statement.

What that statement, and the statue itself, means to the people you encounter is a perfect introduction to the politics that infuse the setting. Some view the statue as the last remnant of a glorious monarchy, while for others it is a reminder of the failures of the revolution to achieve anything substantial, and for others still it is solely a misguided project by ignorant bourgeoisie art students.

Utilizing your amnesia as a perfect excuse to ask elementary questions, you are able to put together the backstory of Revachol, drawing in disparate threads colored by each storyteller’s political perspective to weave a tapestry that incorporates royalists, ultraliberals, moralists, communists, and everyone who had the misfortune to be caught in-between.

Revachol was founded as a royal colony, before eventually gaining independence and forming a monarchy of its own. Wealth suffused Revachol in the early days, the king’s rule buoyed by abundant exports. Over time the quality of leadership declined, as has been the fate of several hereditary monarchies on Earth, to the point that the treasury was depleted - by the very king depicted in the aforementioned statue - and the state policies became unbearable for the populace. A brutal civil war erupted between the royalists and a new faction of communists, many lives were ground to paste beneath the wheels of change, and the city became the Commune of Revachol. Monuments and traditions of the old order alike were demolished, and a new government was formed. Their dreams accomplished, the communists saw an opportunity to fundamentally change the order of things, their political ideations finally getting a moment in the sun.

That moment did not last long. Revachol was critical to the world’s economy, and a Moralist Coalition of world governments found the radical politics of the communists far too disruptive. Revachol came under siege, and the communists were dislodged from power. The artillery shells hit heaviest in Martinaise, birthing the craters that litter the streets.

Revachol was put under international supervision, and commerce began to flow again. Order was largely restored, policed by a self-organized Revachol Citizens Militia, an organization that your character would one day join. The city would go on to experience all the ups-and-downs of a capitalist economy, peaking for some decades before entering a recession that lingers still.

Martinaise openly carries the scars of this tumultuous history, from the pockmarked streets to the economic dire straits of the local citizens. The scars live on through the survivors as well, and their stances on what really happened and who was right and who was wrong are integral to understanding the major players and the forces involved. You are confronted by several strong political stances, and are often forced to make a statement in support of or in opposition to what you’ve been told - or you may evade the topic entirely, which is a statement all its own. Every life you encounter has been molded in one way or another by what has happened before, pushing and pulling them along until they have arrived just in time for you to relentlessly question them.

As your character trawls the district in search of clues, you may find yourself in a book store. Now here’s a font of information! You find fantasy novels and detective stories, roleplaying games and biographies of famous people, all of which fill in more blanks. What stories entertain the people of Revachol? What inspires them? The books on sale answer those questions, and more.

On the second floor, you find the worldbuilding aficionado’s holy grail - maps! One of Martinaise, one of greater Revachol, and one of some place named Insulinde. Now that’s a curious one - it depicts a great ocean dotted by a collection of archipelagos. You soon realize that on one of those little dots is your home, Revachol. Up until now your world has been damaged streets and traffic jams, names of far-off places and historical factions floating idly through your head, but this opens up a whole new line of inquiry.

You know that you are here, but just where is here anyway?

Tertiary - Innocence and the Pale

Answering that question will certainly not resolve the central plot, nor will it divulge any particularly instrumental facts about the state of the city you find yourself in. What it could answer, however, are some of the most fundamental questions one could ask.

Where did we come from? What does the future hold? Why bother with anything, when we are smaller than even the smallest dots on a map?

Answers to these questions and more come from two sources you may not expect: a wealthy ultraliberal who has arrived in Martinaise to break the strike, and the ruins of an abandoned church. You will likely encounter the ultraliberal first. Her name is Joyce, and she is quite willing to entertain a wide array of questions, perhaps out of sympathy for your condition. Through her you confirm many of the facts you’ve already learned: Revachol is just a small, formerly instrumental part of a greater world named Insulinde, that world is inhabited by a wide variety of people and cultures, and many of them are descendents of immigrants from another land who traversed a mind-bending physics-defying void to get here.

Wait a minute! Most of that seemed rather sensible, but what was that about a void that sucks the thoughts out of people, drives them mad and causes fundamental laws of reality to fail?

It is here that you learn about the Pale, and a tremendous revelation sets in. All along, you believed you were simply a detective playing his part in a convoluted murder mystery, set against the backdrop of a declining city molded by revolution and counter-revolution. While genre classification can be endlessly debated, I argue that the introduction of the Pale into the background of the narrative takes the setting far beyond a localized criminal investigation into the realm of speculative or science fiction. The genre is defined largely by the questions it asks: how would the human experience change if we invented intergalactic travel, or if we discovered parallel universes, or if aliens arrived to upset the balance of things? Well, the nature of the Pale and the influence it has on mankind’s existence raises an avalanche of such questions, not the least of which is “What if humans were the alien invaders?”

The Pale is a void, in many respects like the inhospitable environment of Space that surrounds planets in our reality. Unlike Space, the Pale seems to be terrestrial, a region that makes up most of the surface of the globe humanity lives on. It is a connective tissue that fills the space in-between the “isolas”, the human-habitable areas with farmable land, drinkable water and breathable air. At the border, matter begins to dissolve into a kind of gray mist. Outside of the isolas, “reality” as humans know it begins to fail. Mathematical principles and physics stop behaving as one would expect up until the point that they do not behave at all, once one has traveled far enough. The Pale can reach above the world’s surface, which interferes with attempts to leave the atmosphere and travel into what we could call Space, limiting humanity to the isolated pockets of existence they call home.

Radiation sickness is a serious concern, which drastically limits the time a person can safely spend traversing the Pale. Beyond physical damage to the body, human perception itself begins to fail, as the human mind starts to absorb the past, drawn together from the unconscious collective of human experience. Memories belonging to individuals long-dead may become your own, and telling the difference between your own lived experiences and your “new” memories may become impossible.

You can encounter someone experiencing these effects yourself, well before you learn of the Pale; a woman stuck in traffic who at first appears senile, largely disconnected from the world as she meanders through the memories that have taken root in her head. She is a paledriver, someone contracted and trained to navigate vessels through the Pale to bring cargo between the isolas. Humans only first successfully traversed the Pale thanks to the invention of “aerostatic” flying ships, specially designed to function where traditional velocity-granting rotors fail far out in the Pale, and “pale latitude compressors”, with which they could use radio powered by isolated repeater stations to compress the space that needs to be traveled on a route between isolas.

I’ll note here that the technology of radio is fully integrated into the setting as a fundamental invention - officers use it to coordinate their operations, people listen to the latest music, and “radiocomputers” use radio waves as their medium for communication and operation - which is an excellent example of how a worldbuilding element can have hooks into many levels of a fictional society.

What is the Pale? Some argue that question is impossible to answer, as it is nothing at all. In many respects it is the absence of every observable feature by which we can define anything, the opposite of anything that is. Others theorize, in large part due to the effect it has on the human mind, that the Pale is a by-product of human activity, an accumulation of history, where experiences go to die.

Humanity at large is foreign to the Insulidian isola, home to the game’s setting of Revachol, with expeditions arriving there just under four centuries before the present day. There is evidence of pre-historical peoples living there - perhaps settling before the Pale? - and the Semenese people evidently found some way to psychically prepare themselves such that they were able to migrate to Insulinde years before the rest of humanity colonized it using advanced technologies. Insulinde changed radically as humanity flocked to the New World, with the species doing what it does best: acquiring resources, building cities and political systems, and creating many problems for themselves. The isola was forever altered, much as would happen if an alien force descended upon Earth and upended the entire order of things, applying an entirely foreign set of morals and standards to a place once free to determine its own future.

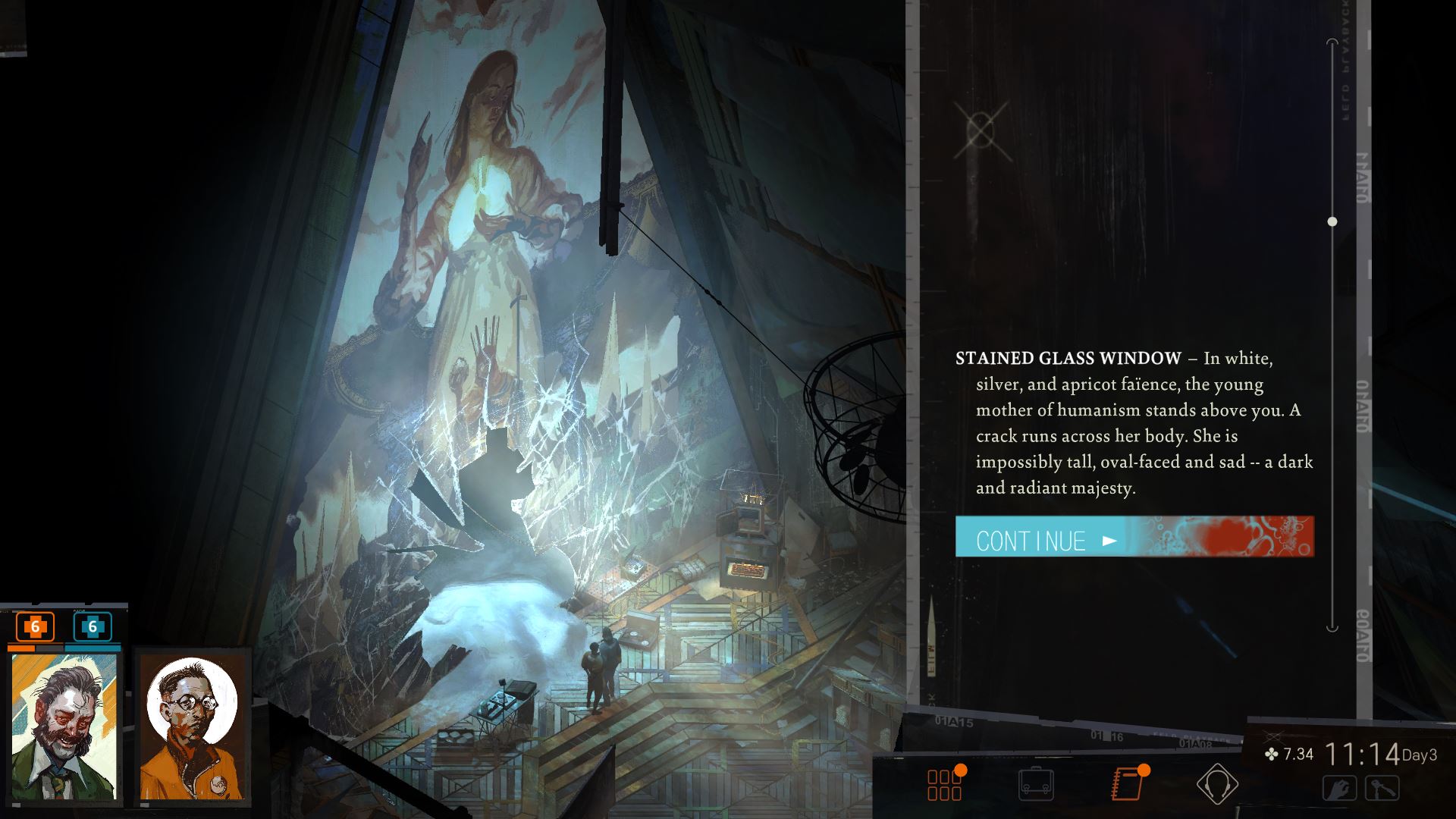

Who or what sparked humanity’s revolutionary journey to Insulinde? Though a variety of cultural factors and leaders throughout history laid the necessary groundwork, there is a singular figure who pushed the human race to the heights needed to change itself forever. You can see her in-game quite easily, if you like. Just travel to the abandoned church off in the western end of the map, walk inside, and peer upwards at beauty and innocence incarnate, deified in delicate stained glass. Her name is Dolores Dei, and she is perhaps the singular most important person in history - if she was a person at all.

Dolores Dei was a politically connected woman in the court of Irene La Navigateur, Queen of Suresne on the isola of Mundi. The Queen gained her titled of “La Navigateur” largely due to Dei’s influence, as she relentlessly pushed for expeditions into the Pale. As Dei gained prominence in the years after discovering Insulinde, she was eventually declared by the Founding Party to be an “Innocence”, just one of six throughout history, and given tremendous political and cultural authority.

An Innocence’s nature is both historic and theocratic, as their time in power is always of such importance that they are viewed by many as a holy culmination of history, the manifestation of trends and forces beyond human control. An Innocence is inheritably infallible, as their decisions are simply not decisions at all, but rather historical inevitabilities accelerated through their guidance. Humanity was driven forwards by leaps and bounds throughout her rule and colonization of the “New New World” of Insulinde - her time of influence so critical that it was referred to as the Dolorian Century.

There are hints, buried deep in the recesses of memory as you look upon her artistic rendering in the church - one of many dedicated to Dolores - that she may not have been so innocent after all. Her husband, whose connections she utilized to maneuver her way into prominence, vanished from the historical record as she ascended. She organized a brutal war against a state looking to remove itself from her rule, and forced relocation and re-education programs on dissenters.

Perhaps most concerning of all are the words of her assassin, one of her personal guards who was driven to slay her due to her “otherness.” It was not just her beauty that was otherworldly - the killer noted that she would forget to breathe for more than ten minutes at a time, and that her body burned as hot as a furnace. She is often artistically rendered with glowing lungs in what is now considered an ahistorical flight of fancy, any reports of such phenomena from her time deemed a form of mass psychosis. Her assassin came to believe that she was something beyond human, a force that decided to accelerate history for its own unknown purposes. In his own words, shouted as he shot her dead, “We were supposed to come up with this ourselves!”

Was humanity pushed forward unnaturally by a higher being, a god or alien determined to alter the course of history of Insulinde and beyond? Was the assassin simply insane, deluding himself into slaying mankind’s greatest champion based on nothing more than a whimsical fantasy? No one alive can say, least of all an amnesiac police officer.

Beyond questions of how and why we have arrived where we are, people often ponder what the future holds for us. For the people of Disco Elysium, the Pale holds a terrible, potentially final answer to that timeless question. The Pale, the absence of reality, is expanding. Slowly, but surely, reality is coming undone as the Isolas give way to nothingness. If the problem is not solved, and there are only a few cursory ideas even being considered as possible solutions, then the future of humanity is firmly finite.

History, with all of its struggles and sorrows, its triumphs and meaning, will end in a void of unreality. That history, in fact, may be the primary contributor to the Pale’s expansion, if the theories previously mentioned as to what the Pale is hold true. It is the graveyard of human experience, and one day it will be all that’s left, a memorial void inhabited only by contextless memories of what once was.

This creeping doom, the absolute END barreling towards mankind and everything it has ever known, is so minimally featured in the central plot it feels like it isn’t even happening at all. People live, and die, in Martinaise regardless of what you discover about the Pale. While nothingness encroaches, babies are born, wars are fought, civilizations and ideologies are toppled, and people continue to litter the streets with the recyclables you turn in for pocket change. Meaning is found in the personal moments - talking with an old man about glory days long past, or consoling a victim after their loved one’s passing, or discovering the truth about who you really are.

In the end - before The End - there are always more pressing, more present, matters to attend to. You are here to solve a murder, after all.